dormspam-the-game

You might have read Kathleen’s earlier blog posts (one, two) about a little thing called dormspam-the-game, an MIT-wide competition with 452 different players across all of campus. This competition had various “game theory”-esque challenges run by anonymous gamemasters and $749 in prizes. If you’re still hungry for more details on this wacky game, never fear, for I was one of the gamemasters and have more content to share :D

For much of the summer, I worked with Whitney Z. ‘21 designing, iterating, and testing this project. The two of us wanted to share how the other side of these games worked: a “behind-the-scenes” tour of everything that it took to make these games come to life!

a history

WZ: Paolo was actually one of the first people I met at CPW. He struck me as somewhat charming, despite his obsession with the color orange,01 and certainly interesting. I’m sort of surprised I ever found him given the low number of course 14s. I gave him my number, but Paolo never texted me back. (I told him this story three years later— he didn’t believe me02 and then found my number in his contacts. I’ve been converted to Messenger, so I guess he won in the end.)

We took 2.00b together, then 14.30 and 14.05 our sophomore year. I’m 99% sure he didn’t realize I existed in 2.00b03 . We somehow re-bonded over psets sometime in either 14.30 or 14.05, and further in 14.19 our junior fall.

There’s two amusing things about Paolo: he enjoys working on not-class things in class,04 and he enjoys being cryptic about them. I stumbled upon Paolo running Next Forum Games, a precursor to dormspam-the-game, in 14.05. I promise this is all (mostly) relevant.

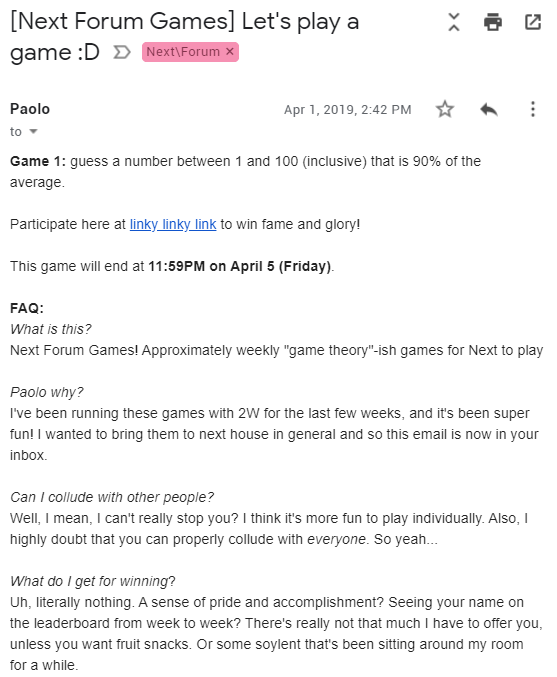

PA: Outside of my room in Next House, I had a 2.5’ x 3.5’ whiteboard that served as a message board—something to share events that are happening and also a way to run fun polls with people in my wing, like “What do you miss most from high school?” or “Draw a snake that ate something.” At the start of my sophomore spring, I started running some games on my whiteboard—things like “Choose a number from 1-100, trying to guess 90% of the average” and “Choose the least chosen of A or B; but, I know you’ll choose A.” People could submit answers by dropping sticky notes into a small box outside of my room, and that was that.

I ran maybe 4 or so of these games and people seemed to like them; so over spring break, I started planning an even bigger version. And on April 1st (why did I decide that date), I sent the following message to my dorm’s email list.

the snark starts early

People submitted their answers and seemed to enjoy; my dorm’s area director (someone whose full-time job is just to help residents) found me and said he liked it so much that he was willing to fund prizes for the rest of the games. I ended up running 5 more of these games, including “Hide and Seek” and “Guess the difference between your number and a randomly chosen partner’s number.” At some point this semester I told Whitney about these games after her many questions05 about the weird spreadsheets I was looking at during 14.05. These games were fun to put on, but after the semester ended, all was done with Next Forum Games.

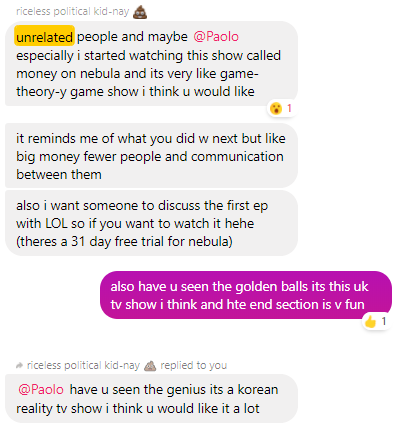

WZ: In May—a full year after the conclusion of Next Forum Games—I had been watching Money, a game show developed by Tom Scott. I was very excited and messaged our 14.19 group chat (named “snek econ kidz”) if anyone wanted to watch with me.

PA: I hope you enjoy Whitney’s nickname in this chat. Brownie points to anyone who can guess what in the world it refers to. My nickname shall go unspoken.06 But anyways, here’s what Whitney sent:

chat log 1/3

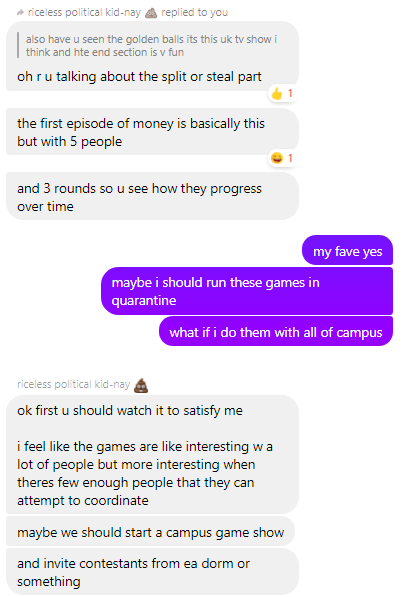

chat log 2/3

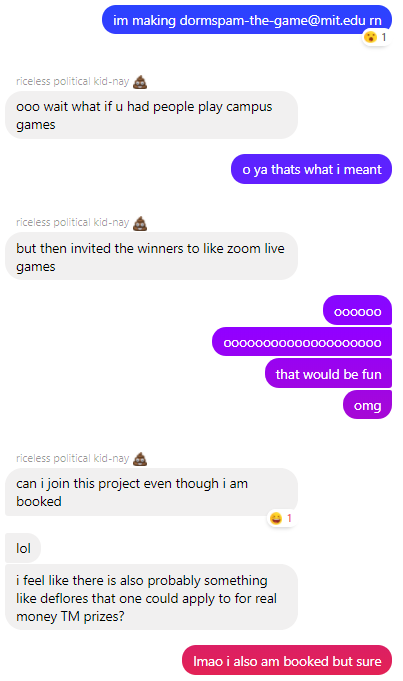

chat log 3/3

And after a while of bouncing ideas off of each other, we decided that we’d try and actually make this all happen.

To clarify, the name “dormspam-the-game” comes from the fact that we’d send out these games over dormspam, the informal name for the set of all dorms’ social lists. It’s the most-used way to reach all of campus to publicize events, clubs, fun polls, or start flame wars.

The start of these games happened very spontaneously. We didn’t have any well-defined goals going into it (which, honestly, is how lots of things in life happen); we just had an idea and ran with it. Our initial conversations involved sketching out different ideas that could make for entertaining and challenging games. We also just wanted to do something to bring a bit of joy and community to people’s inboxes, especially as we’ve all been relegated to the far corners of the earth07 in corona-exodus. It’s really easy to just feel like every day is the same in quarantine, and this was one way to add some variety.

setting things up

We knew that we wanted to have prizes to give away to our participants. MIT students will do a lot for free money, like filling out many of the surveys that hit their inbox. There’s a few different funds at MIT that have money set aside just to help run cool events, including the Baker Foundation and the de Florez Fund for Humor.

As part of the application process for funding, we wrote a proposal for how every dollar would be spent. This meant we needed to think ahead about how each of the games would work and how prizes would be divided. Unfortunately, the Baker Foundation application cycle had closed, but de Florez was still offering up to $74908 in funding and we applied for it. If you really want to examine the historical evidence, read our original proposal here.

We were both immensely excited when we de Florez gave us money:

literally big iff true

To make our whole charade appear just a bit more legitimate, we set up a website at dormspam-the-game.mit.edu. The Information Systems and Technology desk at MIT (more frequently called IS+T) supports a number of different ways to make websites; many students make their own personal websites using scripts.mit.edu.

However, given our lack of website-making knowledge (neither of us are course 6, oof), we decided to use the Drupal Cloud website builder to help us out. Additionally, the Drupal Cloud website builder allowed for webforms that require MIT Certificates to access, making it easier to validate members of the MIT community when they played our games (and so random people on the internet couldn’t just win money).

One of the first pages on our website, the FAQs page, helped us find our tone and style for being Gamemasters. At some point during website building, we also decided that we wanted to be ~mysterious, anonymous Gamemasters~ for the fun of it.

We then set up our first form game, “Game 0: Rate Paolo Out of 10,”09 for our first playtesters: Emily C. ‘22, Dhruv R. ‘21, Faraz M. ’21, and Izzy B. ’21. It turns out that when there’s templates and many things already set up, even people who know nothing about websites can build working websites :D And so we moved on to the real thing™.

game design

For dormspam-the-game, we ran 5 separate games. In this section, we want to just give you a sense of what each game was, some potential strategies to approach playing the game, and how we thought about the results. For each game, we’ve also linked the full game descriptions with the real results.

- Game 1: Hide and Seek. From a list of 20 places, choose one place to hide and one place to seek; your goal is to find the most people relative to how many people find you. Hide and seek isn’t usually thought of as a “game theory” game, exactly. But for a game structured like this, you have to try and predict exactly where people will choose to hide (places where people normally pass through? or never visit?) so that you can choose the best spot to seek, and vice versa for your choice in hiding. It’s the ultimate “reverse psychology” test—can you out-predict everyone else? To spice things up even more, we gave people a few “hints” to naturally draw their attention towards specific places on campus, such as “No one’s in Hayden because it’s under construction. On the other hand, everyone walks through Lobby 7 (or, at least did).” Because we deliberately brought attention to these places, it was natural that fewer people wanted to hide in them. However, some people chose to seek in these hinted places, indicating that they thought people would try to “hide in plain sight.” It didn’t work. Once we had a winner for Game 1, we decided to ask our winners of each game a few questions and post them to our winners page. We did not expect there to be such big beef over pineapple on pizza; shahul’s answers were a welcome, amusing surprise.

- Game 2: Greed control. Choose 5 numbers from 1 to 50; If you choose *k* and that number was chosen *n* times, you receive *k/n* points. Go for as many points as you can. Those of you who frequent math forums might already be familiar with this game from AoPS; it’s basically a more involved version of that. In Nash equilibrium, each number is chosen with inverse proportion to its value; however, following this strategy yourself is unideal because people naturally aggregate towards certain values. In particular, we hypothesize that people shied away from “middling” values and “round” values because they feel less “random”. And this just makes them the better choices for your overall score. ****It was in this game that we got the idea to rebrand the in-game MIT as the Missouri Institute of Taxidermy.10

- Game 3: Division of Student Life.11 Divide 100 points between school, sleep, and social. We selected different metrics for each of 3 rounds, and aggregated them for the final score. This was our most complicated game yet—and probably a bad decision to have run without testing things first.12 Lots of folks commented that they felt that this game was unfair, because in rounds 2 and 3, two players could submit identical answers but score differently, depending on who they were paired with. This brings up an interesting question of what exactly “fair” means. For example, tournament-style games work by pitting individual players or teams against each other. Of all five games, this game most directly forced players to think about tradeoffs and risk. Riskier players chose to place a large portion of their points in one or two categories, whereas more risk-averse players chose to more evenly spread their points across the board.

- Game 4: COVID-90: The Counting of Vacancies in Dormitories. **Players guessed 90% of the average of all players’ guesses. More accurate was better. **Given the complexities of Game 3, we elected to tone things down for Game 4, our easiest to understand game. We were surprised that one player guessed 4000 — since the maximum is 4000, 90% of the average is as most 3,600. The standard deviation of guesses was large, with many players guessing around 3000, and some guessing as little as 0. The pure strategy Nash equilibrium is for all players to guess 0. Intuitively, given what other players guess, each player guesses 90% of that; when all players think this way and continuously take 90% of some value, one reaches 0. Of course, to play in this manner, one has to assume that other players will also play using this strategy, which is clearly not true experimentally. Wikipedia says it best: “This game illustrates the difference between perfect rationality of an actor and the common knowledge of rationality of all players. Even perfectly rational players playing in such a game should not guess 0 unless they know that the other players are rational as well and that all players’ rationality is common knowledge. If a rational player reasonably believes that other players will not follow the [reasoning] described above, it would be rational for him/her to guess a number above 0.”

- Game 5: Institvte FUNdraising. **Players invested coins they held into the FUNd, which multiplied and split investments amongst all players, regardless of their initial investment amount. Players also submitted a number of coins to punish the lowest quartile. More coins at the end was better. **This game is a spinoff of a classic public goods game—more money in the pot is better for everyone, but everyone’s personal incentive is to be a free rider and not put in anything—bar the punishment, of course. At its core though, our implementation of the game boiled down to “guess the lowest quartile” and submit a value marginally above that. Of course, this is difficult and a poor guess could result in a steep loss, so many players elected to invest 0 and voted for the lowest punishment. Like Kathleen, we found surprising the submission that invested 0 but voted for a punishment of 300, as well as the submission that invested 1000 but voted for a punishment of only 50. If you liked this game, Wikipedia is informative about different variations of public goods games, and this paper is also a fun read.

For fun, a few games that didn’t make the cut:

- Guess Course 6: Guess the fraction of the players for this game that are course 6s. Every time someone submitted, their guess would be posted on a public list. Later guesses receive fewer points. With this game, we hoped to test how much people would trust crowdsourced information on the public list. Unfortunately, there was no good way to create this public list with DrupalCloud webforms.

- Guess when the next game is released: The next game will come out 10-15 days from now. Your score is how accurately you predict it. Like the above game, the longer you wait, the better you can guess; however, there’s also a chance that the game ends before you even can submit if you wait longer. In the end, we decided we wanted a regular release schedule and thought that this game would lean too strongly towards luck rather than wit.

- Paired Institvte FUNdraising: Before we came up with the Institvte FUNdraising in its final form, we toyed with an alternate version. Instead of entering an investment amount and a punishment amount, players would enter how much to invest, be paired with a random player, and then submit how much to punish that individual player. However, we ultimately decided that having a multi-week game wouldn’t work out very well.

We had a few people ask where to find games like these and where to learn how to play games like these. To be quite honest, we have no clue. However, you might find something you enjoy in the following list. We don’t claim that this is exhaustive; feel free to add other things that you think would be cool down below :)

- TV Shows

- Money

- The Genius

- Golden Balls

- Classes

- 14.12 (Economic Applications of Game Theory)

- 14.13 (Psychology and Economics)

- 14.44 (Energy Economics)

- 14.160 (Behavioral Economics)

- 17.810/17.811 (Game Theory and Political Theory)

- 11.011 (Art & Science of Negotiation)

- Books

- Thinking Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman

- Nudge by Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein

- Basically any strategy board game

final game

The culmination of dormspam-the-game was a “final game,” where the 5 winners of each week’s contest could compete against each other for even greater prizes. We envisioned this as a 2 hour “game show” to entertain viewers.

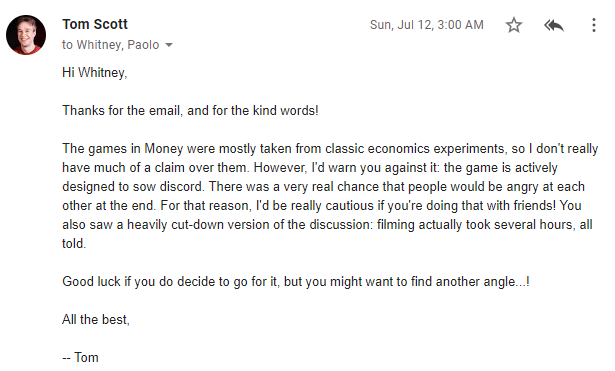

As we hoped to build a game show heavily inspired by Money, we also emailed Tom Scott, the creator of the show, who gave us permission and offered us some advice:

As you now know, we decided to take the luck instead of the advice to do something else.

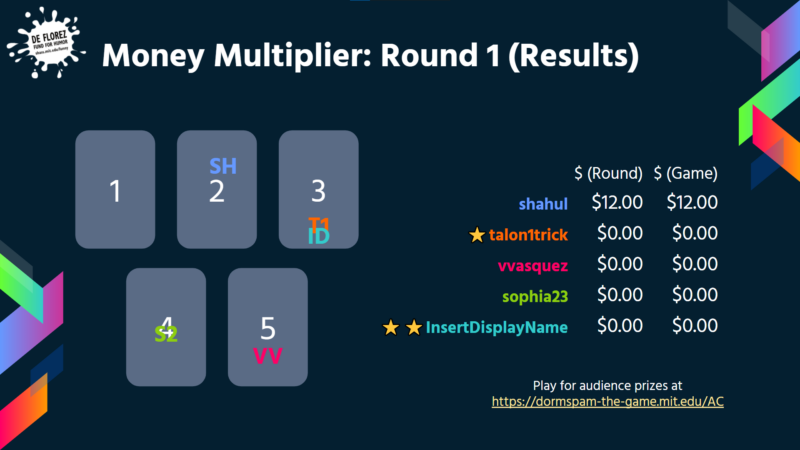

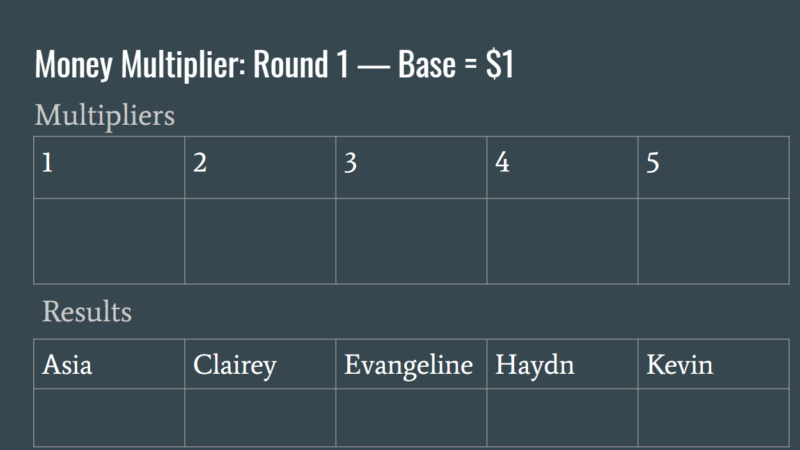

Our initial show had 4 separate games—Negotiation (NG), Money Multiplier (MM), Public Goods (PG), and Endgame (EG)—with 3 rounds each. In each round, players could win both dollars (which they could just take home or transfer to other players) and stars (which players were told would be useful for EG, but couldn’t be transferred and had no inherent worth). We revealed player earnings—with names attached—after each game.

The overall strategy for these games is quite interesting; a fully cooperative set of players could collectively take home all of the money in each game and split it evenly. While defecting from the group in each game could net you a bit more money in the moment, it also eroded trust and makes future games of trust much, much harder. A quick overview of each game and some strategies:

- NG: Players choose one of 5 cards, each with a specific reward. They receive what’s on that card if they’re the only one that chooses it. Some rewards had negative dollar amounts, while others had stars on them. A fully cooperative team would try to designate one person to choose each (positive) dollar amount, then transfer money so that it’d be split equally. However, the availability of stars complicates this strategy, since they can’t be transferred to other players, and no one has a sense of how much they’re worth.

- MM: Players choose an integer from 1 to 5. If they choose the lowest unique number they receive some base prize that is multiplied by their integer. For example, if the base prize was $5 and players chose 1, 1, 2, 2, 3, the person who chose 3 would receive $15. The person who wins the most money in this round gets a star. The optimal cooperative strategy is for exactly one person to choose 5, and everyone “doubles up” on lower numbers, so that the prize is multiplied by 5; then, the money can be split evenly between everyone. However, a defector could easily choose a number lower than 5; say that people chose (5, 4, 4, 3, 3); someone could (anonymously) choose 2 instead of 4, and walk away with $10 for themselves instead of only the $5 they’d get from collaborating with the whole group.

- PG: Players contribute money to a communal pot. The pot is multiplied by some multiplier (larger than one) and then shared evenly among everyone. The person who wins the most money in this game gets a star. Conceptually, this game is a lot like Game 5, Institvte FUNdraising. While it’s in everyone’s interest to contribute as much as possible, each person individually does best if they contribute nothing. This game, compared to all others, is highly reliant on individuals trusting each other. As the rounds in this game progress, the multiplier gets even higher, which only increases the incentive to defect.

- EG: One player, the endgame controller, creates a deal to split $150 among all 5 players. In the previous games, players could win money and stars. In Endgame, each star was one vote for selecting the endgame controller. If the deal doesn’t get approved after 3 rounds, then no one takes home any money. (Players didn’t know the structure of this round before starting it.) If players trusted each other in earlier rounds, they could do something fair; however, if there was no basis of trust, then there’s a chance that no one takes home anything in this round.

We knew we only had one shot at running this, so we ran three playtests with feedback sessions afterward to try and create a final game with the dynamics we wanted. Each of these playtests ended up differently, which helped us iterate and iterate again to make the final final game.

Playtest #1: We had an amusing 4 vs. 1 playtesting dynamic here, where four players chose to coordinate with each other against a single player that chose to deviate in the very first round. One of our players broke a few rules to help choose a specific endgame controller, who evenly divided $150 among all players in the cabal of 4.

This playtest also had no centralized systems for sharing winnings with players; Paolo just PM’ed everybody after each round. This didn’t work out terribly well, and so we introduced “dashboards”13 for each player to keep track of their winnings in this game. Click here to see what these dashboards look like.

At this point, we also did a slide revamping so that results would automatically update on the slides. This came along with slide-beautifying, and they look very pretty :) They also match the dashboard theme!

we definitely didn’t use templates… but it’s so pretty

pretty gradients with clip art!

slide of a round in progress from final game

our original theme was a bit less pretty

i am glad we did not use this theme

Previous Next

After Playtest #1, we tried to schedule the real game for the following weekend, but due to conflicts, ended up with a date 3 weeks later. In hindsight, this was very lucky for us in terms of producing a better game, as it gave us time to run two more playtests.

Playtest #2: This test started off seeming like it’d follow the same storyline as the first one. But, one of our playtesters convinced everyone that they weren’t playing against each other, but rather competing against us to try and win as much money. With that in mind, these people trusted each other completely and took home almost every single dollar14 that we had to give out in prizes. We maybe should have seen this coming—the one player who got screwed over in Playtest #1 later messaged Whitney that he only played as he did because he misunderstood the rules.

We thought this wouldn’t make for good entertainment for our audience, and so we tried to incentivize distrust a bit more. Based on a suggestion from Jesse O. ’16, we made the revelation of winnings after each game anonymous so that people could bluff about how much money they had. We also reordered the games to PG, MM, NG, EG, as PG has the most opportunity to “fake out” the other players with respect to how much money you placed into the pot, and so could sow discord earlier.

Playtest #3: With all of that, we tried a third and final playtest one week before the final game actually happened. This playtest was by far the most chaotic of the three, with total earnings of $61 (which included no deal made in the Endgame). The game ran slightly over, so we decided to cut MM and EG each from three rounds to two.

We were a bit concerned about low earnings for the real deal, but thought that real money would pressure players into deciding a deal for Endgame, so that everyone would at least win $150. We also started designing live “Audience Contests” to help us engage with our audience, where they could make guesses about how the final game would go in real-time to win the money that the players didn’t earn.

We are immensely grateful to all of our playtesters,15 Andrew K. ’22, Arushi O., Asia C. ’20, Clairey Y., Emily C. ‘22, Evan T. ‘19, Evangeline K., Haydn B., Henry K. ’17, Izzy B. ’21, Jesse, Kevin L. ’19, Nathaniel K. ’19, Sarah M., and Sarah P. ’20. We tried to avoid using current MIT undergraduates for playtesting, so that they could fully enjoy the live show. This turned out to be somewhat difficult, and a reminder of how MIT-based our friend groups had become. We had to dive very deep into family friends and people we knew from high school.

So with all of that, we were ready for the real finale: the final game. The two of us were definitely anxious about how it’d go; despite all of the work we put into testing (probably 20 hours of work for us each), we really only had 3 data points we were using to build our final game—all 3 of which gave different results. We sent it out over dormspam (duh), did so many last-minute script changes and slide edits, and on Friday, August 21, the grand finale finally happened.

The final game ran about as well as we possibly could have asked for. There was a great balance between people trying to deceive each other and people trying to get everyone to collaborate; the 5 players took home $256.18 out of a possible $399 in winnings. There were a few hiccups (big and small) during the final game, but overall, we think it went spectacularly. We seriously think that watching this video replay is really entertaining, so if you’re in need of just under 2 hours of good fun content, click above. We gave live commentary about the final game as it went, so we’ll absolve ourselves of writing more about it here. Go watch!

fun tidbits about these games

Mistakes

These games did not run perfectly; nothing ever runs as planned, and there were many, many things that didn’t go as planned throughout these games. Some highlights of the mistakes that we made:

- Game 3: Our initial results were completely wrong; we used a different scoring system than we had said in the rules. We “fixed” it and they still were wrong, so we had to send out another correction; luckily for us, it didn’t change who the overall winner was.

- Game 4: We missed an error on our website that meant we didn’t actually record the usernames of people that played. This confused many people and we needed 100 people to resubmit their responses :(

- Game 5: We gave instructions in words about how we would calculate scores, but then added in a formula version of it to appease the math majors. The formula was wrong. We got corrected by (not) math majors.

- Final Game

- Our forms for Negotiation didn’t have the correct numbers on them, requiring us to change the forms in the middle of the game.

- Similarly, the forms for Endgame controller voting had names from our previous playtest. Oops.16

- We had to calculate the winners of the Audience Contests live, and we goofed and read off the wrong names at first. Oops. That was definitely the most stressful part of all of this but we ended up getting them right after a few minutes of frantic spreadsheets.

And so we weren’t the completely perfect gamemasters that we wanted to be, but honestly, we think we did pretty well for 2 MIT students putting this on in their spare time outside of work :)

Dolla dolla bills

One of the hallmarks of dormspam is that any email sent out to all of the dorm social lists needs:

- To have the mailing lists bcc’ed

- To have the text “bcc’ed to all droms” or some variant spelling of this phrase

- To include the color of your underwear as “[color] for bc-talk”

The third one might stand out as a bit of a weird one; take a look at this post for some history and this one for some data. But regardless, we were indeed dormspamming, and we needed an underwear color. Now, many people who dormspam an event include some colors which are a bit “out there”, such as:

- Zoom blue

- AlexaFluor-647 red

- Coquelicot

- None

- Road stripe yellow

- Synthetic ultramarine

- Purell clear

It is (purell) clear some of these are less legitimate colors than others—many people simply choose to name a color that’s somewhat related to the event that they’re sending over dormspam. We had to sign off on our emails somehow, so naturally, we said dolla dolla bill green for bc-talk.

However, we do not want you to think that we are like any of those plebians who lie about their underwear color for an amusing thing on the bottom of dormspam. No. Because Paolo, in fact, sent our dormspam while wearing dolla dolla bill green underwear.

to my knowledge, i am the first person to post my own underwear on the blogs

The magic of QUERY

If you don’t know how to use the “QUERY” function, you need to learn it. It’s seriously so powerful. From an array, you can select specific columns, rows that match certain criteria, sort by specific columns, transpose your data, or even calculate averages or maxima for specific groups. Calculating our winners became as simple as a formula like

=query(Import!R:AD,"select AD, R, AC, S, T, U, V, W, X, Y, Z, AA, AB where R is not NULL order by AC desc")

which, in the realm of spreadsheet formulas, looks very, very pretty.

Zoom streaming

It turns out that streaming a game on Zoom isn’t easy for a lot of reasons. Here’s some weird things that we did in order to make the stream actually work.

- To show a timer to the players, Paolo set a virtual background that was just a video with a 5 minute timer.

- All of the results that appear on the slides are linked to a “master dashboard” that Paolo had; updating them required you to press an “update content” button on that slide.

- This button didn’t appear when you shared the slides as fullscreen, so Whitney had to just show the slides as if she was editing them. But there’s a problem with this: players can see the slide previews and potentially get information they shouldn’t have. To solve this, we used jank Javascript code to hide the slide previews.

- Paolo tried to live-monitor chat as it happened to send links to the live Audience Contests and to explain games and strategies. This got harder as the stream went on and things got more chaotic.

the end

Neither of us expected that a lightbulb moment in May would carry us through 3 months of ideating, planning, testing, and, of course, gamemastering. It’s been a big rollercoaster of a ride, from joy to anticipation to “oh shit” (in both excitement and dread).

We’ve loved every single comment we’ve received in the feels box. Whitney is happy that no one attempted to submit the Bee Movie script. Paolo would be happier if someone had tried.

For anyone that played, we hope that we’ve made you do a bit of a think, appreciate being at the Missouri Institute of Taxidermy (or that other MIT), and most importantly, brought about some light-spirited fun. The two of us had a lot of fun running dormspam-the-game this summer.

And with that, we take off our Gamemaster hats17 for one last gamemaster goodbye.

Comments